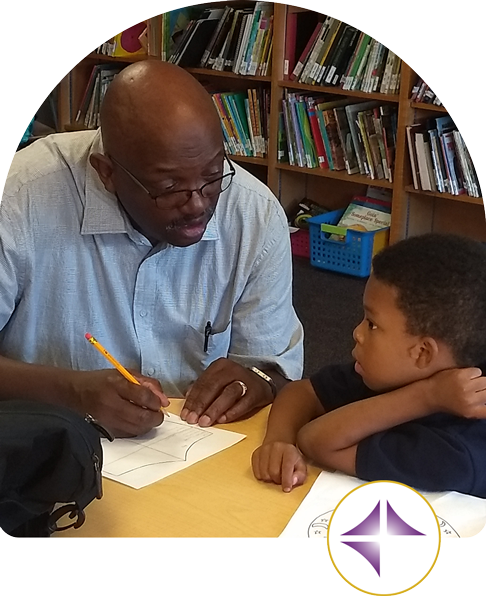

IVC is a community of faith-driven changemakers making a difference across the country. Here, we share inspiring stories from our corps members, reflections on Ignatian Spirituality, and updates on IVC’s growing impact.

We honor the dedication of our corps members who embody the spirit of service in their communities. Their stories reflect a profound commitment to social justice and the transformative power of faith in action. Join us as we explore the remarkable journeys of those who are making a lasting difference in the lives of others.

Explore the latest stories below!

Be the first to receive IVC news, inspiring stories, and spiritual reflections—right in your inbox.