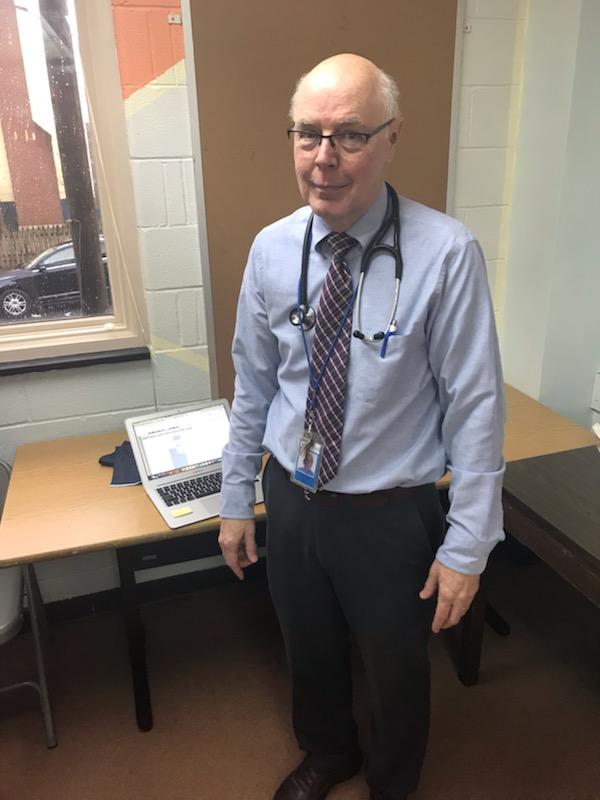

Dr. James Goedert works at Catholic Charities Anchor Mental Health in Washington, helping to care for people suffering from poverty and mental illness. Photo courtesy of Anchor Mental Health

When Dr. James Goedert comes up with an idea, people pay attention. That’s because his ideas save lives.

As a doctor and senior researcher at the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, Goedert’s ideas were pivotal to the race to understand, treat and prevent HIV/AIDS. It was his ideas that uncovered how to reduce the risk of passing HIV from a mother to her unborn child. It was his ideas that dared hope a person infected with HIV could still live a full life, if only the right medicines were developed. And it was his ideas that sought a way to slow, if not prevent, the spread of the disease.

Today, Goedert’s ideas are still saving lives and giving hope — not as an eminent NIH epidemiologist but as an IVC volunteer at Catholic Charities Anchor Mental Health in Washington.

At both the Cancer Institute and at Anchor Mental Health, Goedert’s work has centered around caring for the sick and unwanted of society. In the early days of the the AIDS epidemic, it was gay men and IV drug users. Today, it is the mentally ill on the streets and in prisons.

“The populations are only superficially different,” Goedert says of caring for the AIDS patients during his years at NIH and those who come to him now at Anchor Mental Health. “The individuals are marginalized and have enormous needs.”

And just as his ideas changed the lives of people affected by and infected with HIV, his ideas about caring for poor, mentally ill patients in Washington are helping to establish a system that will help improve and save their lives.

Doing Good with Other Good People

Goedert came to IVC as many volunteers do: through a blurb in the church bulletin. When he retired from his 36-year career at the Cancer Institute, he and his wife, a retired attorney, knew they wanted to remain involved and active. So in 2016, after a two-month, post-retirement vacation at a waterside cottage in Ireland, they began their volunteer assignments — he at Anchor Mental Health and she to an organization that assisted people seeking asylum in the United States.

“IVC seemed a good match for our interests: two-days-a-week service combined with religious and social aspects,” he says. “It helped to identify a community of people with whom we’d have something in common.”

Volunteering had always been a part of Goedert’s life. Even when he was busy with his research at the Cancer Institute, he found time to care for patients at the Spanish Catholic Center in northwest Washington once a month. It not only kept his clinical skills sharp, it gave him the opportunity to directly serve people in need.

This hands-on care for people was never far from his mind even in the midst of his research. “I treasured our ‘clinic’ days in Manhattan and downtown D.C., when I and my NCI colleagues met one on one with gay men and their highly varied reactions to the epidemic and to our efforts to make a difference,” he says.

It made sense, then, that his assignment with IVC began at the same Spanish Catholic Center, serving as a primary care physician to people who were uninsured or under-insured. When another clinician who spoke more proficient Spanish came to work with Catholic Charities, he transferred to the agency’s Anchor Mental Health clinic providing the same primary health care to people suffering mental illness.

The Pressure to Save Lives

Anchor Mental Health serves people who subsist at 200 percent of the poverty line or below, says Marsha Peeks, deputy director of Adult and Children’s Clinical Services at Catholic Charities. Mental illness coupled with poverty often leaves them homeless or sharing space in publicly run group homes. Often they are in and out of jail.

Goedert serves in two ways at Anchor Mental Health, Peeks explains. One is to conduct routine physicals for patients and the other is to serve as a liaison for Anchor’s Health Homes Program. The program allows Anchor to provide a kind of one-stop health service that includes mental health, primary care and dental services.

Goedert works with a team of doctors and nurses to coordinate the wraparound services, a critical program for a population who may not follow up with doctors, or who may be constantly on the move, or who can be noncompliant with their health care.

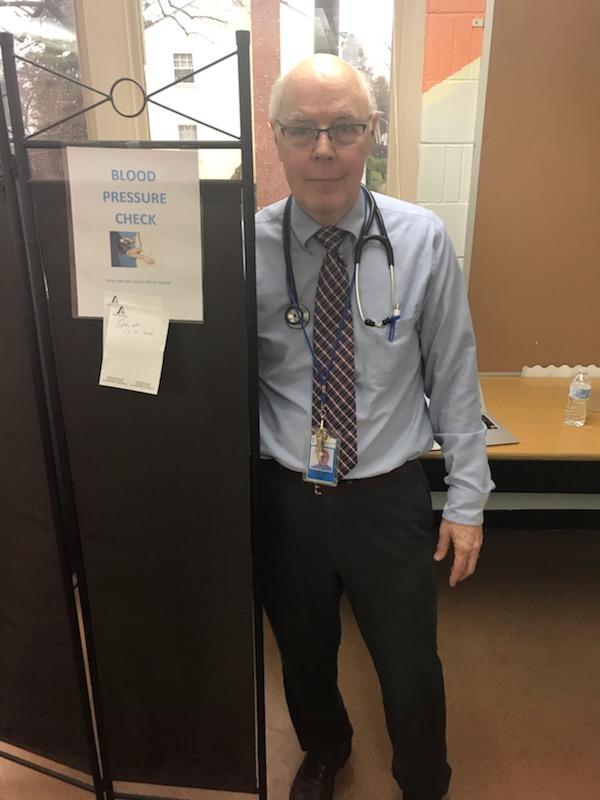

Goedert set up a blood pressure screening station at Anchor Mental Health’s cafeteria to extend the screening to as many clients as possible. Photo courtesy of Anchor Mental Health

Peeks says Goedert’s ideas are already changing how the agency is able to provide basic care. For example, he set up a blood pressure screening station in a place visited by many of the agency’s clients — in the cafeteria, where the agency serves up a hot breakfast or lunch.

“He set up the station in the cafeteria on a table, behind a partition with just a laptop, and started doing blood pressure checks,” Peeks says.

In one instance, his screening detected a client whose insulin levels had skyrocketed to 800 (normal levels are below 100). He was rushed to the hospital and received the care he needed before it was too late. “He really averted someone getting really, really sick,” Peeks says.

He is helping to establish protocols for caring for clients as well as for administering treatments like vaccines. His presence allows Anchor to provide timely care such as conducting physicals that are often required for clients to secure housing. Having Goedert on site eliminates the extra step of scheduling a future appointment and avoids a client losing housing because of the delay.

Goedert has also begun working with the IT team and senior administrators to improve the accuracy of the patient’s physical medical diagnosis. Together they are trying to classify common, potentially deadly conditions as well as track whether patients are receiving adequate followup after a hospitalization or visit to the emergency room.

“We’re not just putting information in [patients’ medical records], we are pulling out useful data,” Peeks says. “It has the potential to change how we are providing care.”

Comforting the Afflicted

Goedert is matter of fact about his contributions at Anchor. “The current primary care (at Anchor) is a revolving door. Doctors keep coming and going … there’s no simple solution,” he says. “I just make sure the screening steps are done, and that I identify the most serious problems and refer them to specialists.”

He is equally matter of fact when he adds, as an aside, that he also continues to volunteer for the Cancer Institute, editing and reviewing manuscripts. Those scientific papers written by and with colleagues cover such life-altering topics as cancer, malaria, hepatitis and HIV. They will influence the world’s thinking on those diseases.

Still, there’s no hyperbole in the connection he makes in his work with patients, whether they suffer from AIDS, cancer or mental illness.

“I was a psychology major undergraduate, but the connection to the subsequent decades was probably my recognition that I liked caring for cancer patients,” he says. “My thinking: most of them I can’t cure, but all of them can get relief from pain, other debilitating symptoms, loneliness and stigma.”